My Four Favorite New-To-Me Discoveries of January 2024!

Hey, Classic Film Fans!

I hope the new year has been treating you well and you’ve discovered new favorites in the past month! I sure have, and I wanted to take a moment to share some discoveries that I found in January with you. There are a handful of honorable mentions that I left off this list, such as Panic in the Streets (1950), Bombshell (1933), Three on a Match (1932), Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939), Queen Christina (1933), The Spiral Staircase (1946), and Blood on the Moon (1948)1. Still, they are all well worth your time, so if you see them pop up on a streaming service or sale from your favorite physical media distributor, I highly recommend checking them out! Some of these films may receive a full-length review in a future newsletter.

ONE LAST HONORABLE MENTION BEFORE WE DIVE IN…

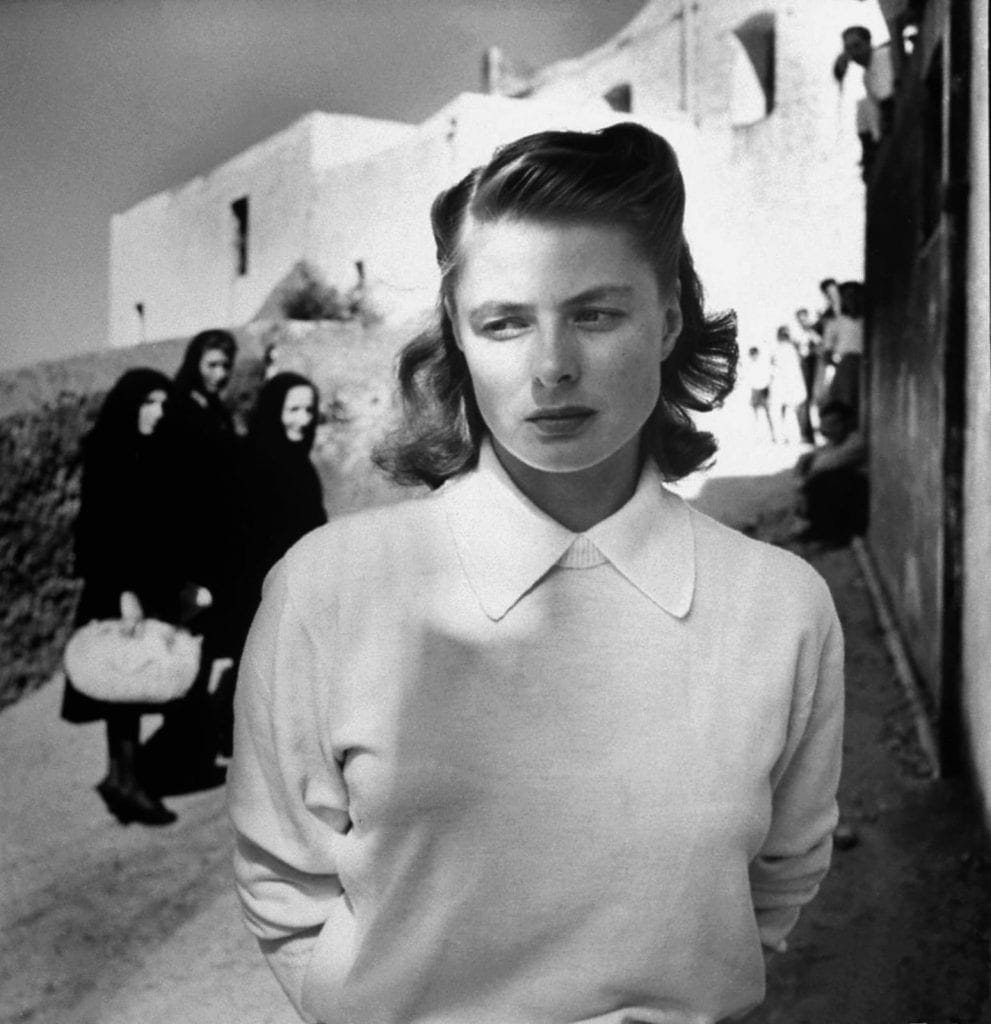

Before I share my four favorite new-to-me discoveries of January, there's one more honorable mention. As I wrote in my previous newsletter, one of the journies I planned to embark on was shoring up my blindspots in Ingrid Bergman’s filmography. I started the year strong by watching most of Ingrid Bergman's collaborations with her ex-husband, Roberto Rossellini, through the 3 Films by Roberto Rossellini, Starring Ingrid Bergman box set from Criterion.

As history is written, after watching and being touched by Rome, Open City (1945), and Paisan (1946), Bergman wrote to Rossellini about her admiration for both and how she would love the opportunity to make a film with him. Shortly after that, Bergman was cast in their first feature film together, Stromboli (1950), and during production, they began an affair, eventually leading to their marriage and a creative collaboration that produced five feature films.

I was familiar with Roberto Rossellini’s work beforehand, having gone through another superb box set by Criterion, Roberto Rossellini’s War Trilogy, last year. However, his films with Ingrid Bergman, especially Stromboli (1950), Europe ‘51 (1952), and Journey to Italy (1954), are different in that they’re all experiments in combining Italian Neorealism with Classical Hollywood filmmaking. The plots of these movies are thin. However, I was surprised by how emotionally invested and spiritually moved I was by the end of each one.

While none of these films were financially successful and ruined Rossellini’s reputation with most critics and the public at the time, many critics-later-turned filmmakers of the Cahiers du Cinéma, such as Éric Rohmer, François Truffaut, and Jean Luc-Godard were adamant supporters of his work. They considered Journey to Italy (1954) the film that kicked off the French New Wave.

After watching each film, I wrote a semi-detailed review of each one (spoiler-free). You can find the reviews on my Letterboxd by clicking on each film title here: Stromboli (1950), Europe ‘51 (1952), and Journey to Italy (1954). While it’s hard to recommend these films to everyone, I think if you’re a fan of the French New Wave or are interested in seeing Ingrid Bergman in a new light separate from her Classic Hollywood image, you’ll find something here to appreciate.

Where to Watch Stromboli (1950) Now

Where to Watch Europe ‘51 (1952) Now

Where to Watch Journey to Italy (1954) Now

Now, to my four favorite new-to-me watches of January…

THE LUSTY MEN (1952)

Every month, I make it a point to check the list of films leaving the Criterion Channel at the end of the month. When I discovered a film directed by Nicholas Ray and starring Robert Mitchum, two of my favorites, was leaving soon, I knew I had to watch it before it was gone.

The film follows a retired rodeo champion turned ranch hand, Jeff McCloud (Robert Mitchum), who crosses paths with a young couple, Wes and Louis Merritt (Arthur Kennedy and Susan Hayward). Wes Merritt, having aspirations of becoming a rodeo champion, enlists Jeff McCloud to train him against his wife’s wishes. As we follow Wes’s ascension from ranch hand to rodeo champion, Jeff McCloud finds himself drawn back into the dangerous and seductive world of rodeo.

The Lusty Men (1952) is an atmospheric and intelligent deconstruction of the American Cowboy, tackling themes of ambition and toxic masculinity (machismo). The film is well known for its realistic portrayal of the rodeo lifestyle, and to bring that realism to the film, Robert Mitchum learned many rodeo tricks for his role. One of the standard practices for riders at the time that he learned, such as lying still after being thrown from a bull, isn’t even used anymore, given how ineffective and dangerous it is; when considering that in the context of this film, it makes its message even more poetic.

While the ending is a bit predictable, it’s still enjoyable. I’m starting to think Nicholas Ray never made a lousy film2.

Where to Watch The Lusty Men (1952) Now

BACK STREET (1932)

Another film leaving the Criterion Channel at the end of January that I wanted to catch was John M. Stahl’s 1932 picture, Back Street. Since taking a class on the pre-code era, I’ve been on a little bit of a pre-code picture kick. The more films I watch from the pre-code era and the 1930s, the more I realize it was one of the best decades for women filmmakers. Of course, it wasn’t perfect; these films were made within a patriarchal structure, so limitations exist. However, it gave women numerous opportunities to depict various powerful and dynamic roles on screen and delve into feminist themes that seemed to disappear from films by the end of the 1930s3.

Back Street is a fantastic melodrama starring Irene Dunne, who falls in love with a married banker (John Boles) and sacrifices her life to become his mistress. While no one will argue with you that the premise is a bit dated, the film is more intricate than it appears at first glance.

Besides exploring themes of love and sacrifice, it also examines the limitations placed on women in society. While, on one hand, Dunne’s character is independent and defies social conventions in pursuit of her desires, the film also reinforces the idea that women should be selfless and willing to give up their happiness for men.

I struggled with Stahl’s understated style at first with such films as Magnificent Obsession (1935), but the more I’ve watched his filmography, the more I’ve come to appreciate it. His camera is mostly static, but the way he can conjure emotions simply with performances and his shot selections is truly remarkable4. Similar to my experience with the Rossellini films I discussed previously, I’m surprised how much this film crept up on me emotionally by the end. I highly recommend checking it out.

Unfortunately, it’s not streaming anywhere as of the date of this newsletter, but I’m sure if you snoop around the internet, you can find it somewhere.

STAGE DOOR (1937)

It's wild that this film isn’t discussed more among Classic Hollywood fan circles. Boasting a cast with a glittering array of stars such as Ginger Rogers, Katharine Hepburn, Gail Patrick, Andrea Leeds, Lucille Ball, Eve Arden, Ann Miller, and many more, Stage Door (1937) depicts the lives of aspiring actresses in a theatrical boarding house during the Great Depression. It’s a brilliantly acted and powerful story of finding friendship in a theater world that ruthlessly pits artists, particularly female artists, against one another.

The director, Gregory La Cava, was renowned for his improvisational style. For this particular film, it is said that he spent his time on set between takes getting to know each of the actresses in the cast. He would then spend the night before the next shooting day rewriting the dialogue to incorporate the actresses' personalities into their respective characters. There’s one line in this film, however, that I doubt was improvised or rewritten that has stuck with me long after watching, delivered by Kay Hamilton (Andrea Leeds):

“How do you know who’s an actress and who isn’t? You’re an actress if you’re acting, but you can’t just walk up and down a room and act. Without that job and those lines to say, an actress is just like any ordinary girl trying not to look as scared as she feels.”

If you’re a theater lover or a fan of anyone in the cast, you need to watch this ASAP.

Where to Watch Stage Door (1937) Now

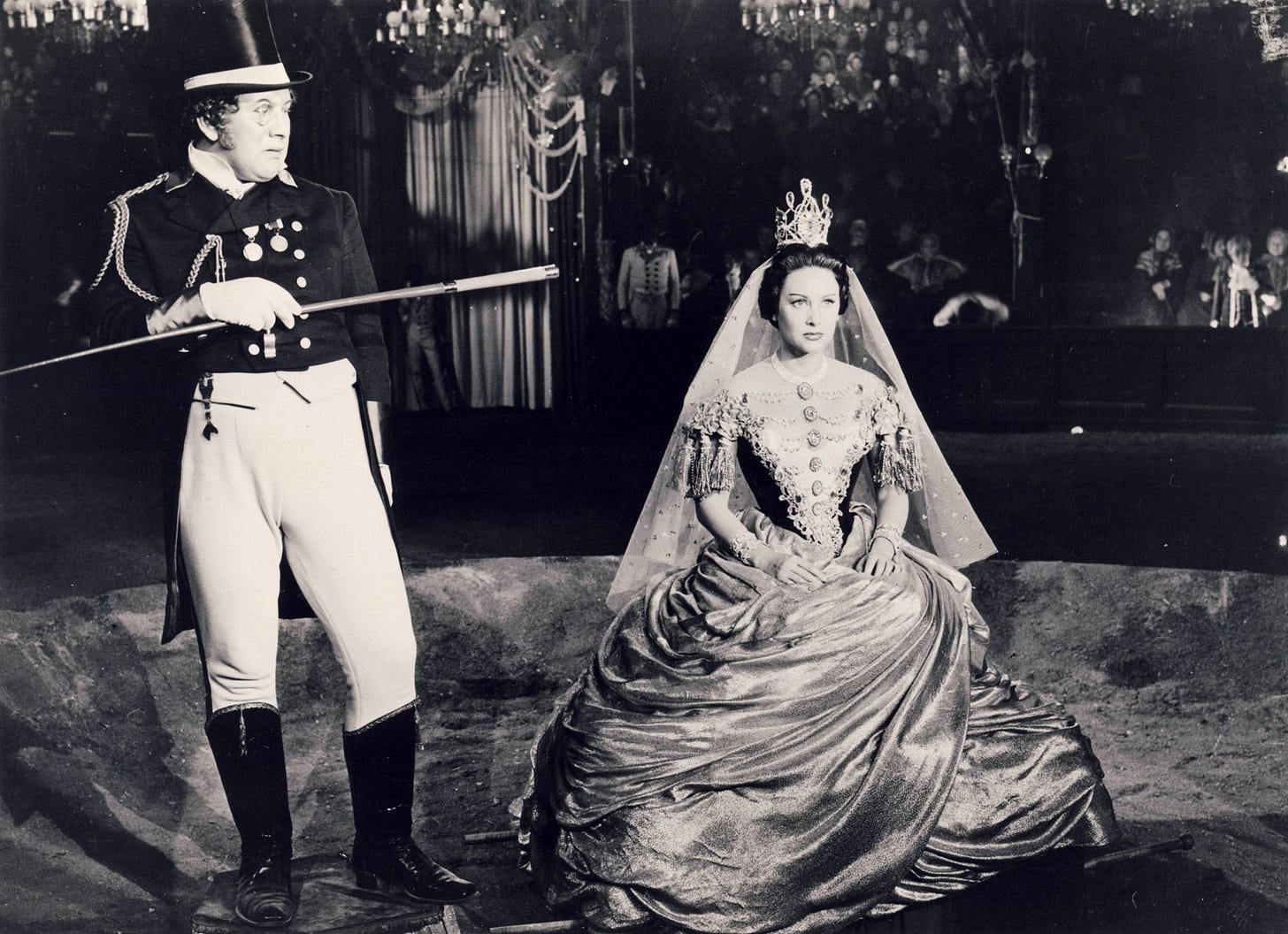

LOLA MONTÈS (1955)

Shot in CinemaScope and lush Technicolor, Lola Montès (1955) is a narratively complex work of art that critiques societal expectations and the pressure of fame.

Based on the story of the real-life figure Lola Montès, a famous 19th-century dancer and courtesan, the film begins towards the end of Lola’s life, where financial difficulties have forced her to become a performer in a circus and reenacts scenes from her scandalous life. As we watch the show, we are treated to flashbacks of the events unfolding in real time in Lola’s life.

Before watching this film, I had only watched one other Ophüls film, The Earrings of Madame de… (1953), which is brilliant in its own right (and a PTA favorite). Still, Lola Montès (1955) was undeniably my favorite of the two5. The fluidity of Ophüls’ camera movements and those famous long tracking shots of his are a dream and perfectly capture the “imagined” freedom and happiness of the titular character and the rotating gears of soulless capitalism that has turned this woman’s life into a product for consumption. Lola Montès (1955) certainly has to be on the list as one of the most narratively innovative films, along with Citizen Kane (1940). The final shot of this film is gorgeous yet heartbreaking.

Where to Watch Lola Montès (1955) Now

Have you watched any of these films before? What are some of your favorite classic film watches so far in 2024? Comment below and let me know!

Until next time, stay safe, be kind to yourself, and continue watching great films! Thanks for reading!

You can read my brief reviews for each film on Letterboxd by clicking on the titles!

He probably made a clunker at some point, but please let me live in this perfect world for a little longer. Thanks.

Of course, there are exceptions. See Mildred Pierce (1945).

The film doesn’t even have a score, which makes it even more remarkable.

For the record, Bong Joon-ho agrees with me.