Time flies by fast. A couple of weeks ago, I was driving back from Los Angeles after attending my second-ever TCM Classic Film Festival (TCMFF). As with any exciting trip coming to an end, the drive back took longer than the drive there. I didn’t want to leave.

In the weeks after returning home, I've missed queueing up in lines and striking up random conversations with fellow classic film fans. I've missed sitting in theaters, watching on loop the always wonderfully produced TCM and TCMFF promotional videos before each screening, and eagerly awaiting the introduction to the film by a TCM Host and possible guest. Finally, I miss the sound of applause every time a classic film fan favorite appears on the screen. There's nowhere else in the world where you’ll get a packed theater clapping for the likes of Chester Morris, Wallace Beery, and Jimmy Conlin.

My recap of this year's TCMFF was longer than expected, so I've split it into two parts. In this newsletter, I recap my experience on Thursday (4/18) and Friday (4/19), the first two days of TCMFF. On Friday (5/10), I will publish the second part of my recap, covering Saturday and Sunday of the festival. Be sure to subscribe for free if you haven't already so you don't miss it!

If you read my previous newsletter, highlighting my initial picks for TCMFF, you'll notice below that I veered a bit off the original plan I set out for myself, but I think it was for the better.

THURSDAY (4/18)

On Thursday, I started my festival at the Egyptian Theatre with White Heat (1949) in 35mm. I had never been to the Egyptian Theatre before, even before its renovation, so it was exciting to finally see and experience one of the oldest theaters in Hollywood. The inside of the theater was beautiful, and while it felt modern, it still evoked a sense of history and tradition.

Eddie Muller, the Czar of Noir, introduced White Heat (1949). Before watching the film, Eddie gave us a nugget about how James Cagney occasionally went "off-script" and improvised, much to the vexation of his co-stars, especially Virginia Mayo, in this film. After you watch White Heat (1949) and witness some of the actions she was on the receiving end of, you realize why she was "terrified" at times to work with him.

Eddie also mentioned that many people inappropriately misclassify this film as a gangster picture. He thinks it’s more akin to an outlaw film, given there’s no syndicate. Having now watched it, I agree with Eddie. His thoughts on this film as an outlaw picture rather than a gangster one are similar to what I thought after watching another Walsh “gangster” picture, High Sierra (1941), a couple of years ago.

Overall, I enjoyed the film and thought James Cagney's larger-than-life performance suited the big screen well.

Next, I booked it to the TCL Chinese 6 Theatres Multiplex to watch The Small Back Room (1949). The Archers are a filmmaking team I've always adored, and I attribute their masterpiece, The Red Shoes (1948), as one of the films that helped rekindle my passion for classic film. Their mixture of history, culture, landscape, romanticism, and the fantastical in their films has always intrigued me, and it’s all there in this lesser-known work.

The Small Back Room (1949) teams up Kathleen Byron and David Farrar again after starring in Black Narcissus (1947) as wife and husband as they work through their relationship troubles amidst the threat of a new booby-trapped bomb introduced by the Germans in England during World War II. Much more grounded and tighter than the masterworks that came before it, The Small Back Room (1949) is still a riveting watch, and amongst the bleakness, I found it quite romantic. Watching it without seeing German Expressionism's influence on Powell is impossible. While the film doesn’t have as much fantastical quality as some of the films before it, it still has fantastical moments, with one scene reminding me of the dream sequence from Spellbound (1945).

I think there’s a lot to love here for fans of the Archer who have seen most, if not all, of their most well-known works. I think it’s an underrated gem. But I would recommend going into it expecting more of a kitchen-sink British drama rather than a technicolor epic. But make no mistake; this is still an Archers film through and through.

This screening was the U.S. premiere of the restoration performed and supported by The Film Foundation and Rialto Pictures. I don’t claim to be a restoration expert, but the picture was gorgeous. Since this film has been released by Criterion in the past and these two organizations have a relationship with them, I wouldn’t be surprised to hear an announcement that it is being released on Blu-ray from Criterion soon.

FRIDAY (4/19)

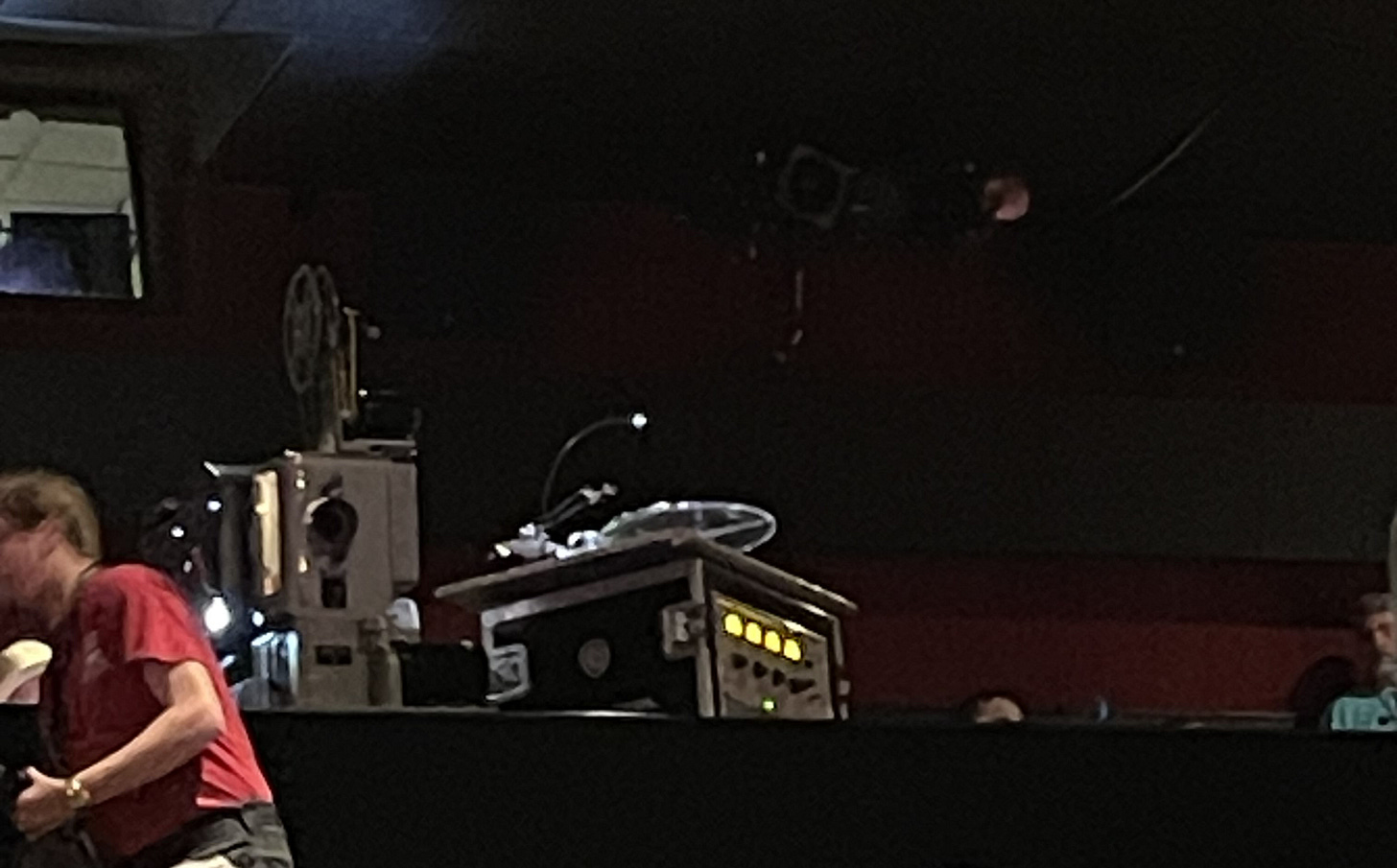

While I wanted to visit El Capitan Theatre for the first time, I started my Friday morning by witnessing history instead by attending the “That’s Vitaphone!: The Return of Sound-on-Disc” presentation by Bruce Goldstein, Steve Levy, Bob Weitz, and Shane Fleming. For the first time in more than 90 years, six Vaudeville shorts were projected in 35mm, with sound playback from their original 16-inch discs! The turntable used to play the discs was designed and engineered by Warner Bros. Post Production Engineering Department and is the only one known to exist.

Introduced by Warner Bros. in 1926, Vitaphone was one of the earliest sound film systems developed by Western Electric and Bell Telephone Laboratories. The system used a separate record to store sound, synchronized with the film during playback. While Vitaphone as the industry standard was short-lived and eventually replaced by sound-on-film technology in the late 1920s and early 1930s, it revolutionized the film industry by paving the way for the transition from silent films to “talkies.”

The presentation started with an amusing (not intentionally) 1926 introduction to Vitaphone by Will H. Hays, the first president of the Motions Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) and father of the Hays Code established to regulate moral standards in Hollywood. While leaving the theater after the presentation, I heard someone say that Will Hays ‘looked like one of the animatronics in The Hall of Presidents at Disney World.’ I haven’t gotten that picture out of my mind since. See for yourself below:

Bruce Goldstein, Steve Levy, Bob Weitz, and Shane Fleming provided much-needed information about Vitaphone's history, preservation efforts, and how the turntable was engineered and designed to play these 16mm discs. Bruce Goldstein mentioned that this presentation was ‘the closest to experiencing a Vaudeville show from the 1920s’.

After the discussion, they played five more Vaudeville shorts, with a few other digital shorts from the 1920s in between, to allow the audio engineer from Warner Bros to prepare the next reel and disc. For a very practical reason, it was an ingenious move, as it was impossible not to notice the difference in audio quality between the two. I couldn’t believe how much detail I could hear from those 16-inch discs!

The five Vaudeville shorts played were My Bag O’ Trix (1929), The Ham What I Am (1928), The Beau Brummels (1928), Lambchops (1929), and by far my favorite of the bunch, Sharps and Flats (1928) starring Myrtle Glass and Jimmy Conlin, who would later join Preston Sturges’ famous troupe of character actors and would appear in seven of his films.

Instead of attending a discussion at Club TCM initially as planned (maybe next year!), I decided to get in line early for the screening of Three Godfathers (1936) in 35mm at the infamous House 4 of the TCL Chinese 6 Theatres Multiplex. The film was introduced by Leonard Maltin, a legendary film historian and critic. I have admired him for years, and his Classic Movie Guide has sat next to my TV for many years.

The Three Godfathers (1936) is the fourth of five adaptations of the popular story from Peter B. Kyne’s novel of the same name. This was the first version of the movie I had ever watched, and I was surprised by how dark and bleak it was. However, I did love Bob's (Chester Morris) redemption arc throughout the film and the glimmer of hope that the ending provided.

I decided to do a Chester Morris double feature and catch The Big House (1931) in 35mm, often described as the film that gave birth to prison genre films. Jake Flynn, the son of the late author and film historian Cari Beauchamp, introduced the film. He shared some beautiful thoughts about how much TCM and the festival meant to their family and also some interesting tidbits about the making of the film.

One of those interesting tidbits included how screenwriter Frances Marion, who would win an Oscar for this screenplay and be the first woman to win one in a non-acting category, visited San Quentin State Prison in northern California to research prison conditions and use those details in her screenplay. This echoes Virginia Kellogg's research process for the film Caged (1950) I wrote about in March.

The film was good, but I wouldn’t say it was one of my favorites at the film festival. Still, I enjoyed Wallace Beerey, who practically steals every scene, and the climactic action sequence, which seemed extraordinary for the time.

I saved the best for last. I ended my day by attending a screening of one of my favorite Hitchcock films, Rear Window (1954), at the Egyptian Theatre. The film was presented from a beautiful 35mm IB Technicolor print. I was amazed at how vibrant the colors looked throughout the film, particularly the blue eyes of Jimmy Stewart and Grace Kelly. You could easily get lost in them. Witnessing Grace Kelly's kiss to awaken Jimmy Stewart at the film's beginning left me breathless.

Given how much I love Rear Window (1954), I won’t write much about my thoughts on the film here because I plan to cover it in a future newsletter. But what stuck out to me during this viewing was how much information Hitchcock communicates through his visual storytelling. I wish more modern films and TV shows would learn this cinematic language because nowadays, more often than not, it feels like they’re laden with exposition dumps because they don’t trust audiences to pick up the details. If a studio or filmmaker is reading this, trust me: we’re smarter than you think.

Eddie Muller introduced the film in conversation with Michael De Luca, Co-Chair and CEO of Warner Bros. Motion Picture Group.

That’s it for Part One of this TCMFF recap! Be sure to subscribe below so you don’t miss Part Two of my recap, where I write about watching my first Nitrate print, the world premiere 4K restoration of North by Northwest (1959), Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and The Searchers (1956) in 70mm, Mel Brooks, and a surprise celebrity attendee at one of my screenings!

Until next time, stay safe, be kind to yourself, and continue watching great films! Thanks for reading!